Notes from Suzanne Collins and Suzi Wells on using the ABC cards in Bristol. This talk was given at the ABC mini conference, UCL, London, 9 March 2018. See the ABC Learning Design web pages for further resources.

Suzi: Trialling ABC as a tool in workshops

I first came across the ABC curriculum design method while browsing UCL’s digital education pages looking for ideas. It immediately appealed. My background is in structuring and building websites, and I had used paper-based storyboarding in that context.

First trial: a single unit

Colleagues were enthusiastic and we started looking for contexts to trial it. An academic approached us with a view to involving us in significantly redesign a unit and we suggested the ABC approach.

As a tool for discussion, and for engaging a more diverse group of people – two academics, two learning technologists, one librarian, and someone else – it worked very well. They were very engaged and all could contribute. Although they couldn’t agree on a single tweet.

But we didn’t complete all the activities in the time. We also didn’t talk to them about how it should fit in to the overall development cycle and didn’t have much opportunity to follow up on what next. To me it felt like there was less value in talking about a single unit in isolation, that there would have been more benefit if we’d been working on a programme.

It was a useful tool and an enjoyable session but it wasn’t right yet.

Second trial: developing online courses

Not long after that we were asked to get involved in developing three online courses which would be promoted to our own students, as well as to the public more widely. Each course would be developed by a group of academics from a variety of different disciplines, many of whom had not worked together before.

The timescales were extremely short (by university standards). The academics involved were extremely busy with their existing work. These courses had to be innovative, transformative, cross-disciplinary, interlinked, approachable by anyone, essentially self-sustaining … and should encourage the development of transferable skills. No small ask.

Having pitched their ideas and been selected to lead or participate, the teams were assembled for an initial one day event. As part of this we ran several short sessions. We asked them to do an elevator pitch (they resolutely failed to follow the instructions on this). We also did a pre-mortem (imagine it’s a year down the line and these projects have been an absolute disaster, tell us what went wrong – very popular and a great way of surfacing problems and clearing the air).

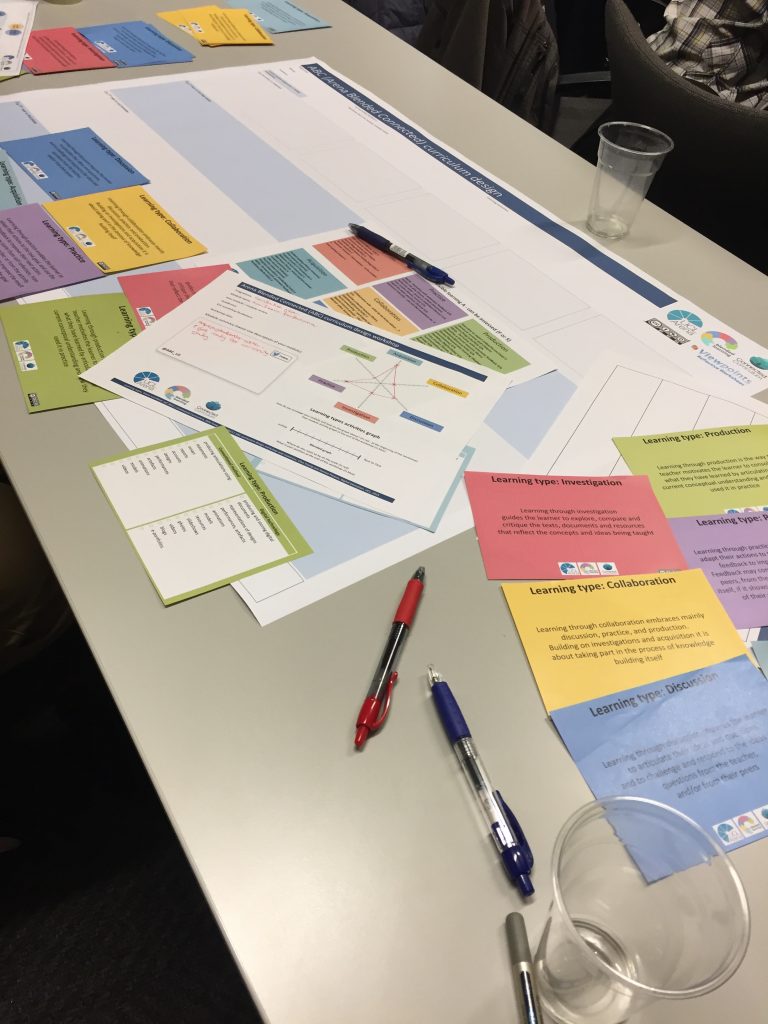

We then ran an ABC workshop, with three tables myself and my colleagues Roger Gardner and Mike Cameron running a table each.

We modified the cards slightly to make them more platform-focused. We also added a time wheel to each week. Students would be expected to spend three hours a week in total on these courses and from conversations we’d had with the academics we knew that they were veering towards providing three hours of video a week (plus readings and activities). We wanted to focus attention on how students would spend their time.

We attempted to fit all this within an hour, because that was all the time available in the schedule.

For stimulating discussion, getting everyone to contribute, and shifting focus towards the student experience it worked well. The teams understood it and could work with it quickly. We were definitely over-ambitions about how much we could get through in an hour. Added to this, it was too early in the process and teams still had divergent or vague ideas about content (even on a big-picture scale) which couldn’t be resolved in a short time available.

One interesting finding was about the value of pushing people through the process. The other two facilitators used the framework and cards but took a more freeform approach, allowing discussions to run on. I was much stricter, pushing people through the activities. At the end of the day my group were the only one who asked to take the cards away and declared that they would use it themselves. Working through all the activities seemed to help people see the value of the process (though of course that may not mean that the discussion was more valuable).

Suzanne: Using ABC throughout online course design

My experiences of using the ABC method came later in the process of developing these online courses. My colleague Hannah O’Brien and I worked intensively with the three course teams, and we turned to ABC to help us do that. When we started, there were a lot of ideas, too many in fact(!), and we tried to find ways to get those ideas somehow on to paper, so that we could all evaluate them, and work them into a course design.

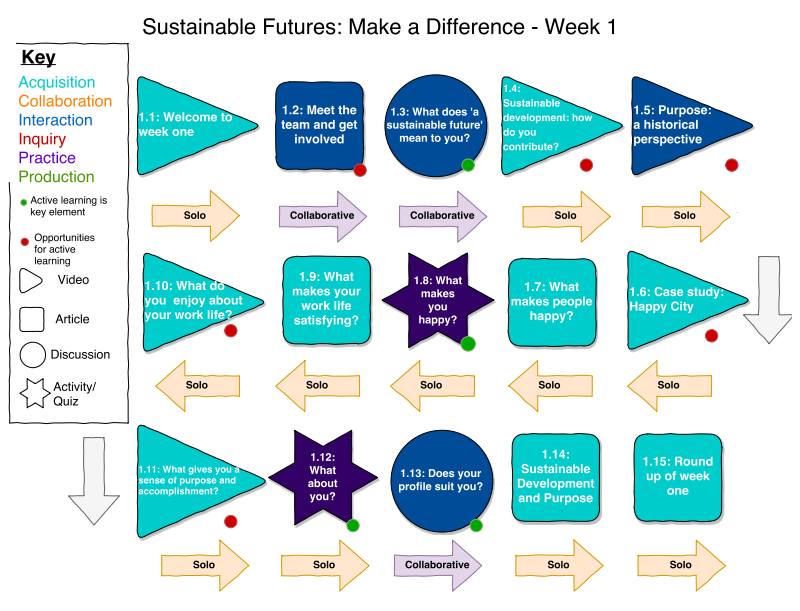

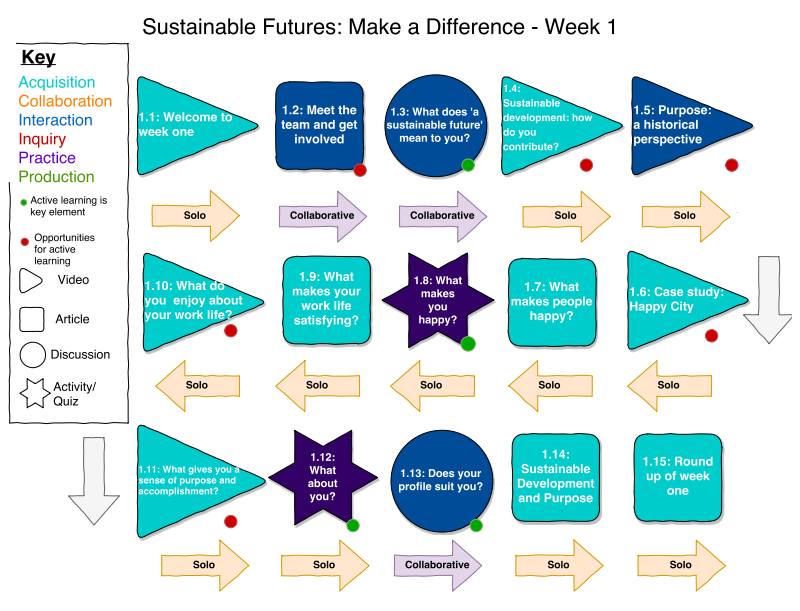

We ran a series of shorter, small group ABC sessions, using the modified cards from Suzi and Roger’s previous session. The courses were going to end up in the FutureLearn platform, so the course design by nature needed to work in a linear sequence of weeks of learning. In each week, we needed a series of ‘activities’, which were made up of different ‘steps’. Anyone familiar with FutureLearn can tell you that there isn’t a great deal of choice for what these steps are: a text article, a video, a discussion, a quiz, or a limited selection of external ‘exercises’.

What the ABC sessions highlighted early on for our teams was that having lots of video and articles explaining ideas might look jazzy, but is all very similar (and not very active) in terms of learning types. We all noticed there was far too much of the turquoise ‘acquisition’ happening in courses which were designed to develop skills such as communication and self-efficacy.

To help our academics come up with alternatives ideas for how students could, within the limits of FutureLearn, have a more interactive and challenging learning experience, we also created a bank of good examples, which we called our ‘Activity Bank’. As we worked to try and think of ideas for collaboration, or inquiry, for example, we could direct them to explore these examples, and adapt the ideas for their own purposes.

Overall, the ABC ended up being a useful tool to get everyone talking about the pedagogical choices they were making in a similar way. We could map the learning experience quickly and visually, so that we could prototype, evaluate and iterate course designs. It also kept us all clearly focused on what the learners were doing during the course, rather than how amazingly we were presenting the materials.

Since then, I’ve found myself returning to the ABC tools and ideas regularly. The learning type ‘colours’ got quite embedded in our way of thinking and documenting learning designs. They cropped up in a graphic course design map created to demonstrate the pedagogical choices for the online courses (see below), and are now doing so again in a different context.

This new context, and the next big project for me is the Bristol Futures Optional Units. These are blended, scalable, credit bearing, multidisciplinary, investigative units, open to all students, around the Bristol Futures themes of Global Citizenship, Innovation and Enterprise and Sustainable Futures. So, no small ask, once again.

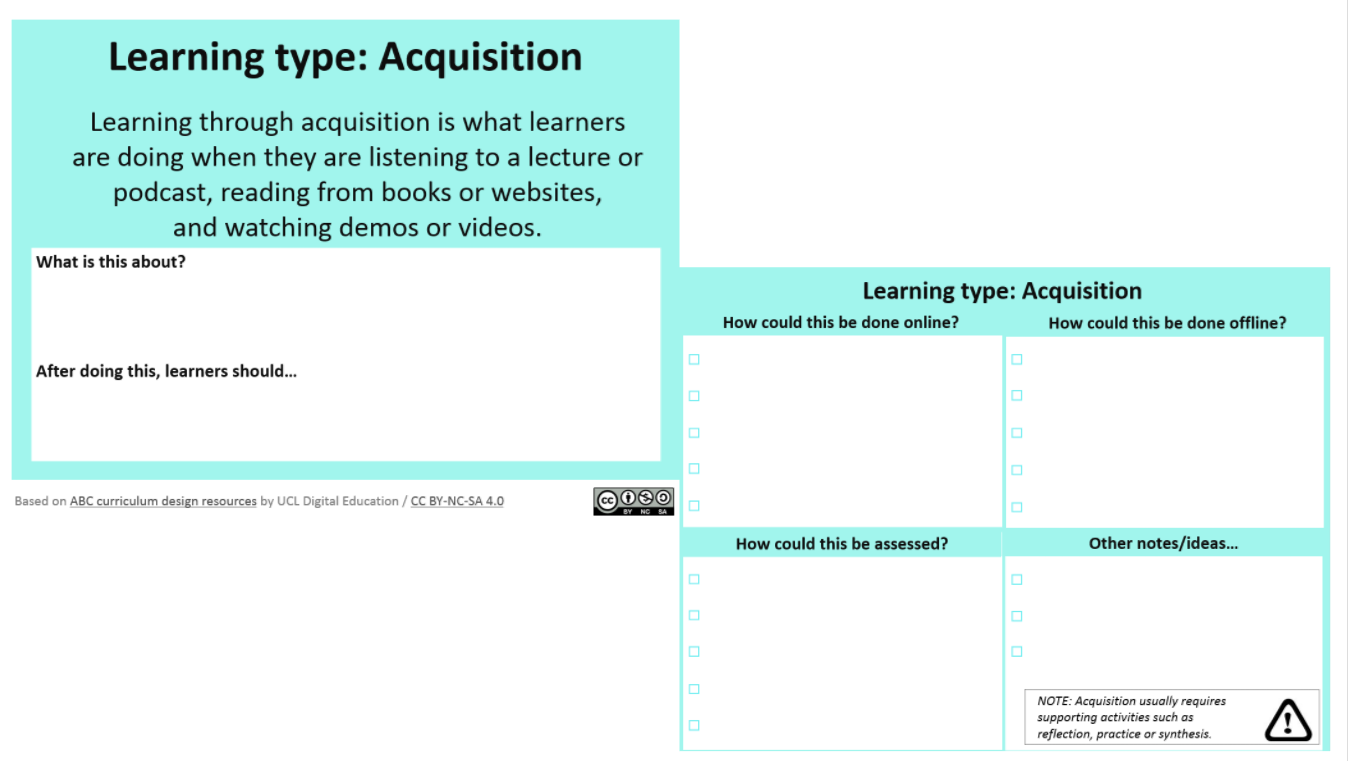

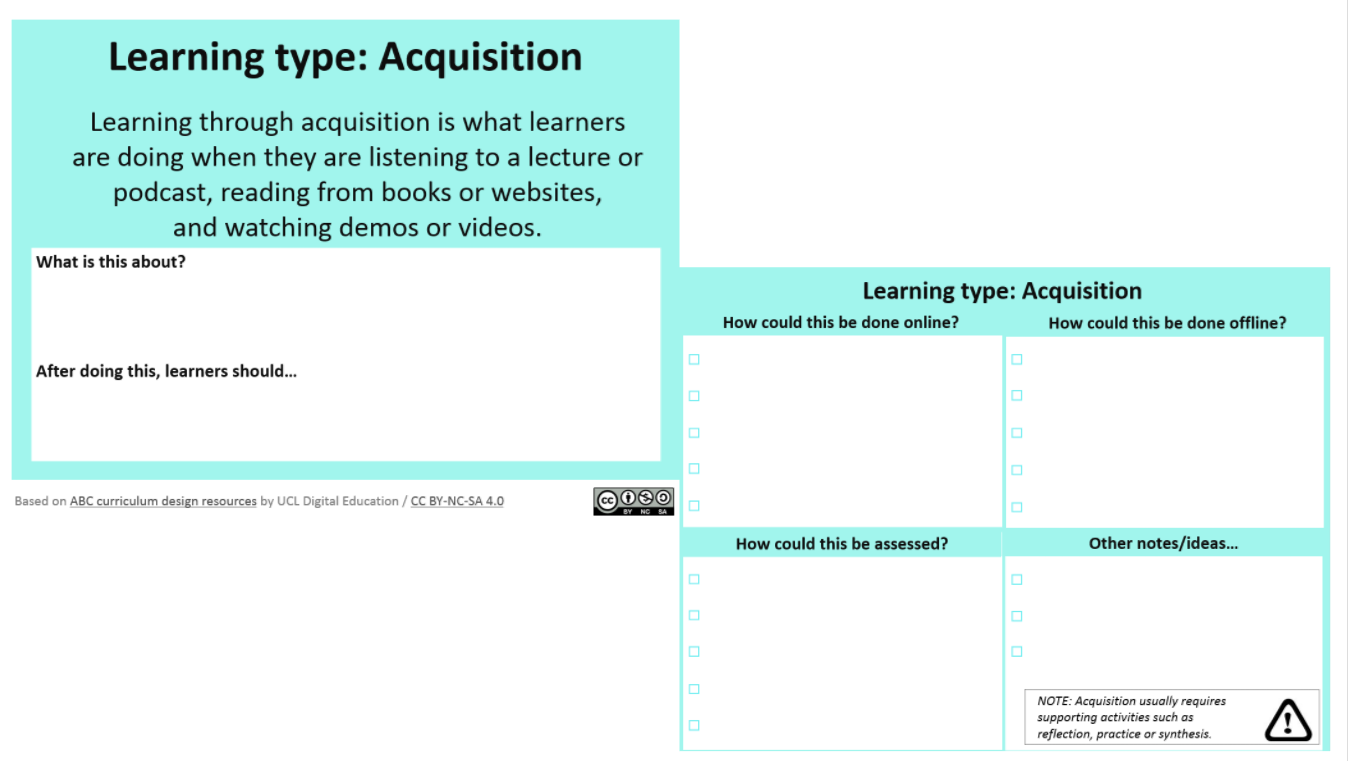

For this, the ABC cards have been tweaked again, this time to generate ideas for both online and face-to-face ideas for course elements, to allow for a flexible and student-choice driven learning experience. How can we provide a similar learning experience for students who might end up taking the unit in very different ways? We’re in the early days of course design, but I imagine that we’ll end up using the ABC workshops in various forms during the coming year!

For this, the ABC cards have been tweaked again, this time to generate ideas for both online and face-to-face ideas for course elements, to allow for a flexible and student-choice driven learning experience. How can we provide a similar learning experience for students who might end up taking the unit in very different ways? We’re in the early days of course design, but I imagine that we’ll end up using the ABC workshops in various forms during the coming year!

In all, the ABC has become a bit of an ace up our sleeves. When we need temas to work more collaboratively, when we need the focus shifted back to the student, when we need to make progress rapidly and efficiently, even when we come to evaluate learning design – the ABC tools seem to provide us with a way to talk, act, design, and iterate.